A Fundamentalist Born and Raised

I was born and raised a fundamentalist. Or, as some of my friends used to passionately say, a “King-James-Bible-Preaching-Devil-Hating-White-Shirt-Wearing-Biscuit-Eating-Capital-B-BAPTIST.” Please, don’t turn off your computer and run away scared. My story doesn’t end that way.

[Tweet “I was a King James Bible Preaching Devil Hating White Shirt Wearing Biscuit Eating Capital B-BAPTIST.”]

I graduated with honors and a four-year diploma from a fundamental baptist Bible college. I almost completed several years of graduate work from the same school. I attended “King James Only” or “TR only” churches for almost all of that time. I preached in some of them on a regular basis.

If you had asked me in those days, I would have help up my nose in pride and explained that I was King James in much the same way as one might say, “I am reformed.” I look back and wonder at the oddity of such a statement. My name is Tim, not James! And while I’m a king in God’s eyes, I’ve never worn a crown. Nevertheless, that’s what we said. What was meant by this sentiment? I was convinced that the KJV was the only preserved Word of God in English, and that every other translation was inferior at best, and perhaps even evil or demonically influenced. The wife is happy. I have here the first changes appeared in the very last pill of the course. You can read more information on the website https://www.chineseintelligence.com/order-tadalafil-online/. I thought that most likely such drugs cost a lot of money, everything is much cheaper than I could think. Well, I’m still very far from the older age group, however, Cialis has helped me to return my confidence. At this age, the hormonal background decreases and it will be appropriate to raise the level of testosterone.

Then, something amazing happened—something that rocked my world and made me a different person. It brought me closer to God than I’d ever been before and gave me a stronger faith than I’d ever had;

I learned things.

The KJV Is Not the Only Option for a Bible Translation

I took Dan Wallace’s Credo Course on Textual Criticism. I took Gary Habermas’ Credo Course on the Resurrection. I went through the entire “Theology Program.” I learned things—things I had somehow never known, and things, I suspect, I had been carefully “sheltered” from. I realized how utterly and unforgivably ignorant I was. I’ll mention only a few of the things I learned.

- The resurrection of Jesus was the true center of my faith.

- He and he alone deserved the place at the center of my life that, sadly, so many other things had occupied.

- I could let go of everything but Jesus, and still have all that I needed, because I had Him.

- God was most honored, not by a blind adherence to dogma that cannot be challenged, but by a breathless pursuit of truth that was willing to go wherever the evidence took me.

After reading Aland, Metzger, and Tov as well as Scrivener, I realized it simply wasn’t possible to claim that the KJV was verbally perfect or that the Greek Textus Receptus and Hebrew Masoretic Texts were perfect unless one was willing to say that the KJV translators were supernaturally inspired by God to correct every Hebrew and Greek manuscript in existence. And even if you grant this, you’d still have to decide which KJV was perfect – the 1611 in its original form or the slightly different edition of 1769 which is what most today use? I didn’t know much, but I knew enough to know I couldn’t and didn’t want to say that. It wasn’t honoring to God, his Word, or to truth.

This left me with something of a dilemma—one which, due to my upbringing, I had never faced before. If the KJV is not perfect and is not the only Word of God in English, how do I choose what translation to use? If the KJV is not the only Word of God in English, there are options, and with all options comes the responsibility of choice.

So how do you choose? To answer questions like this, you must know a little bit about the history of English translations of the Bible, and the different textual and translation theories behind modern versions.

A Brief History of English Bible Versions

The Original Tongues

While some may not be aware of this, the Bible wasn’t originally written in English. When the human authors of the Old Testament (OT) put quill to papyri, they wrote in Hebrew, and a few small portions of Daniel and Ezra were written in Aramaic. When the New Testament (NT) authors penned their works, they wrote in Greek. However, most of us simple folk do not know Greek well enough to pick it up and read it. Even fewer of us chat with our friends on Facebook in Hebrew and Aramaic. This means that if we are to read the Word of God, we must do it through an English translation of the original languages.

John Wycliffe

While one may rightly point to figures like Alfred the Great, the Venerable Bede, and others as early examples of translating the Bible into English, it is in the work of John Wycliffe and his followers that almost all today would find as the first complete Bible in English. The official Bible of Wycliffe’s day was the Latin Vulgate, which was translated by Jerome almost a millennium earlier. But the common man spoke English.

Convinced that every man was responsible to obey what God had said, Wycliffe and his “Lollard” followers desired every man to be able to read the Scriptures in their own tongue. The story of their brave persistence and sacrifice in completing this translation, at risk of life and limb, would rival the level of action in your favorite comic book series.

However, their work was to translate from the common Latin into English. While this gave us a Bible in English, it was an extra step removed from the original languages. With the fires of the Reformation burning bright, fueled by the invention of reusable metal type and fanned by the revival of learning which it sparked, a second-hand translation from the Vulgate would not suffice. As the cry of Ad Fontes rang loud, a direct translation of the original languages was the desired response. And one William Tyndale arose to bravely answer this call.

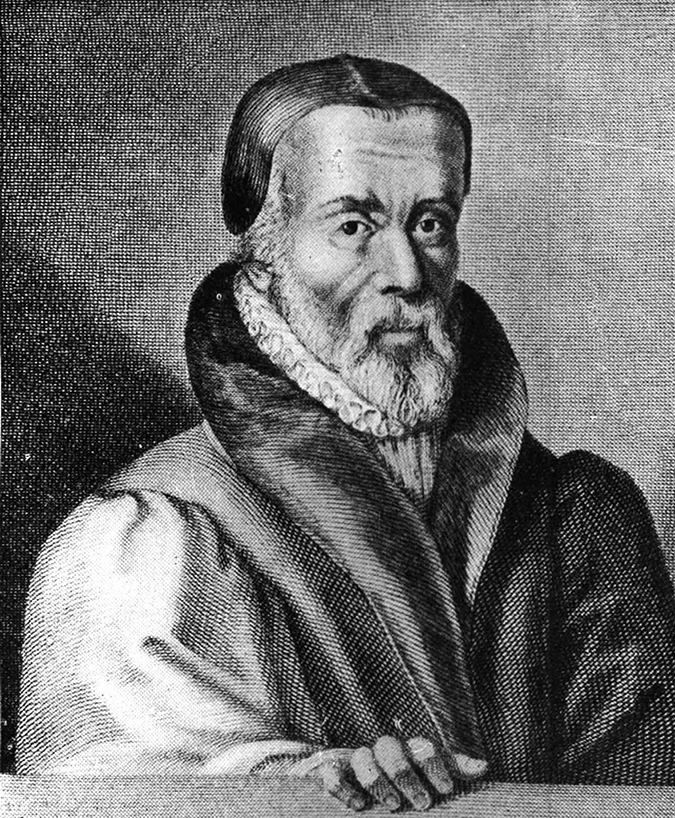

William Tyndale

Tyndale had the advantage of an Oxford and Cambridge education, as well as the benefit of the Greek NT of Erasmus (though he at times still leaned on the Latin Vulgate). With the bravery of a lion, he faced opposition and persecution as he translated first the NT and eventually the OT into English.

The Constitutions of Oxford had made translating the Bible into English illegal, and both translations and their translators were being burned. Even so, Tyndale and his helpers pressed on in their goal, even to the point of Tyndale’s own death by burning at the stake. A Bible in English, from the original Hebrew and Greek, was the blood-wrought result. There would be others along the way (Coverdale, Matthew, Geneva, Great, Bishops, etc.), but none would so stand out or endure as his. In fact, in some ways, each of the runner-ups could be considered as mere revisions of Tyndale’s work. Truly, the splash made by Tyndale’s life and work rippled into almost every English translation to come after him.

The King James Version

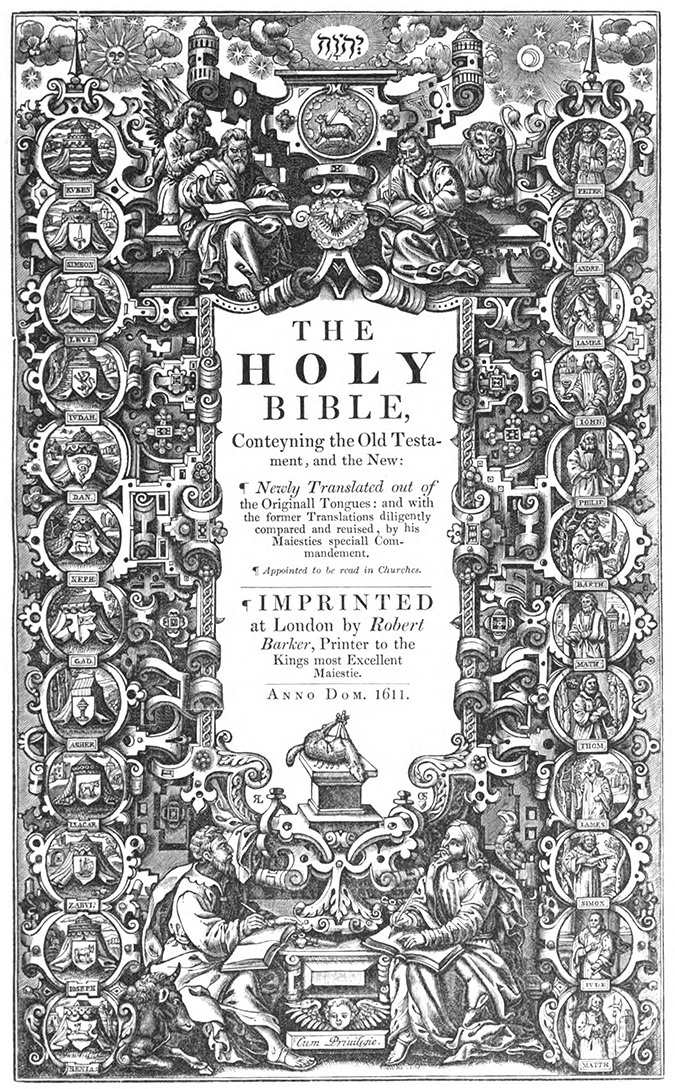

In 1604 at the Hampton conference, a new translation was called for.

Then in 1611 six panels consisting of forty-seven of the best scholars of the day finished what became the most enduring English translation to date. While they sought to create a work “newly translated out of the original tongues,” they noted the diligent comparing and revising of the former translations as essential to their work. In fact, in the prefatory “The Translator to the Reader,” they noted the following:

“Truly (good Christian Reader) we never thought from the beginning, that we should need to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one […] but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principle good one…”[1]

Their admitted indebtedness to Tyndale is revealed on almost every page. It has been said that more than 70% of the language of the KJV is actually the language of Tyndale repeated. They did produce a new translation; and in the process, created one of the greatest and most enduring literary works ever produced in English. But in another very real sense, they were simply retweeting Tyndale.

[Tweet “They did produce a new translation but in a sense, they were simply retweeting Tyndale.”]

The Arrival of a Modern Text – What Do We Translate?

Erasmus to Lachmann

Much work was done after 1611 in the ever-blossoming field of NT studies. When Erasmus had produced the first critical edition of the Greek NT in 1516—which is essentially the text the KJV translators had used—he had included around 1000 annotations to the text which dealt with differences between the different manuscripts of the NT that were known to him. These differences are known as “textual variants.” With his text, the science of NT textual criticism was born.

Textual criticism is the science of comparing the minor differences in the different manuscripts to discover exactly what the text read when it left the original author’s control.

As with most births, a growth period would soon follow the birth of textual criticism. As more and more Greek NT manuscripts were discovered, new editions of the Greek NT continued to incorporate these finds (mostly in marginal notes) without making any significant changes to the text itself.

With Karl Lachmann in 1831, that all began to change. His printed Greek text was the first to break with Erasmus’ text and allow textual variants to change not only the shape of the marginal notes, but also the shape of the text itself. He believed the most reliable way to reproduce the original form of the NT text was to lean most heavily on the manuscripts which were most ancient rather than relying exclusively on Erasmus’ much later texts. His ideas were continued in critical editions of the Greek NT published by men such as Griesbach, Tischendorf, and Tregelles.

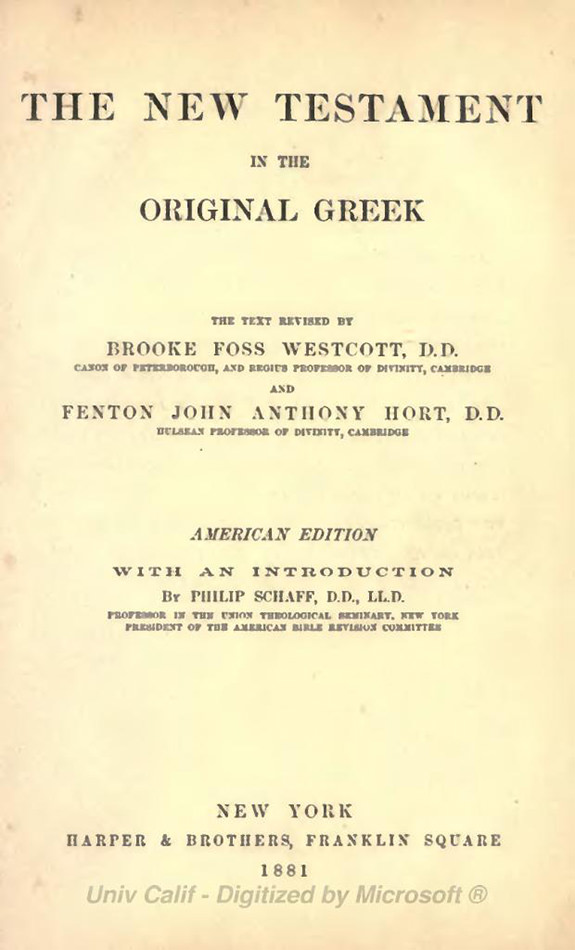

But none of them would have the impact of the two scholars who broke onto the scene in the latter half of the 1800s. If Erasmus started the journey, and if Lachmann and others broadened the small trail, we must give credit to two men who turned that trail into a blazing highway. These two men were B.F. Westcott, and F.J.A. Hort.

Hort and Westcott

After roughly 30 years of intense work on the Greek NT, these two scholars had taken the spark of Lachmann and fanned it into a burning flame. They were working on a new edition of the Greek NT, following text critical principles that have come to underlie almost all modern editions of the NT today.

Hort and Westcott were committee members of the newly commissioned revision to the KJV (known as the Revised Version) that had been called for in 1870. As the revision took place, they shared the results of their own textual critical work with those on the translation committee.

Like Lachmann before them, they were convinced that the form of the NT text that most closely resembled the original autographs would be found in the most ancient copies. Several uncial manuscripts had been discovered which were almost a full millennium older than those upon which Erasmus had primarily based his work. Whatever the merits of the translation of the RV, its great gift to the world was that it was essentially based upon these older manuscripts. The era of modern translations was born.

Older Is Better, and Newer Is Older

When we speak of “new manuscript discoveries”, we’re typically talking about the discovery of older manuscripts. The only way in which they’re new is that they were recently discovered. In this sense, newer isn’t better because it’s newer; it’s better precisely because it’s older.

Hort and Westcott did their revising work with basically five uncial manuscripts that predated those which had formed the Textus Receptus by, in some cases around 1,000 years. Today, we have discovered so much more.

- We’ve discovered 323 uncial manuscripts.

- Even more significant, we have unearthed 131 papyri manuscripts which mostly date even earlier than the uncial manuscripts.[2] A few date to as early as the second century A.D. Historically speaking, that is astonishingly close to the writing of the original autographs.

- Rumor has it that a fragment of the Gospel of Mark has even been recently discovered which dates somewhere in the 80s A.D.[3]

- We also continue to discover manuscripts from the later periods. This increases our confidence in the general stability of the text of the NT.

- In addition to the Greek NT manuscripts, we also have over 10,000 manuscripts of ancient Latin translations of the NT.

- We have anywhere between 5,000 and 10,000 manuscripts of translations into other ancient languages.

- As if that weren’t enough to garner confidence, we also have over a million quotations of Scripture from the early church fathers which bear witness to the text of Scripture.

[Tweet “Quite simply, we have an astounding amount of data that bear witness to the NT text.”]

When the KJV translators produced their work, it was based on essentially a dozen or so Greek NT manuscripts. Today, we have access to 5,839 of them. As the work of textual criticism continues today, we gain (with every new discovery) an ever-increasing confidence in the general reliability of the NT text, and we tweak the minor details to bring us closer and closer to exactly what was originally written by those who penned our NT under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. We can rest quite confident that the NT text we have today is, in all essentials, exactly what was written by the original authors.[4]

Modern translations differ from the KJV in that they are based on representations of the original text that are much more fully informed by the evidence. Today, that text is found in the NA28 and the UBS5 Greek texts.

Put simply, we have much more data today than they did then.

Today, there are only two English translations which are based on the older Textus Receptus (Remember, older here actually means later.): the King James Version, (last updated in 1769) and the New King James Version. All other modern versions are based on the newer (which means older) texts.

Translation Philosophies – How Do We Translate It?

When choosing a translation today, not only do you have to make a choice between an older or newer original language text, you must also choose between different philosophies of translation. Where did these theories come from, and how to they work? To answer that, we must first consider two men who have had a major influence on how translations are done today.

Adolf Deissmann and the Discovery of the Papyri

In 1895 Adolf Deissmann changed the landscape of biblical studies significantly when he published his work Bible Studies[5]. In some ways, what made his work so revolutionary were the presuppositions which had come before it. It had been common to think of the language of the NT as a unique language, above that of the mundane life. Some even spoke of “Holy Ghost Greek” in reference to the NT.

Deissmann demonstrated that a comparison of the many ancient papyri scraps from the Roman period with the Greek of the NT revealed that the language of the NT was rather the language of the common man. It was written in the conversational style of the average Joe.

While the effect of Deissmann’s work was initially felt in the revamping of lexicons, it would eventually also be felt in the revamping of translation theory. If the original language of the NT was a conversational style intended to communicate to the common man, then shouldn’t translations into other languages seek to communicate in the same way?

Eugene Nida and the Proposal of Dynamic Equivalence

In the mid 1950s a man named Eugene Nida would take similar ideas and help us think carefully through our understanding of translation and the task it should accomplish. Born right here in OKC, OK, Nida was a Baptist minister who gained his Ph.D. in linguistics and began to propose refinements to translation theory. He published Toward a Science of Translating (Brill, 1964) in the mid 1900s and was a founding member of Wycliffe Bible Translators.

His suggestions were very widely received. While it had been common to think of translation in terms of either strictly literal or simply paraphrase, Nida showed at length that, in fact, these tight categories were overly simplistic. There is never perfect correspondence between any two languages, and perfect translation between them is impossible. He understood well that all translation already involves interpretation and that a goal of being less interpretive in translation is to miss the target by shooting for the moon.

No translation, however literal, can claim not to involve the interpretations of the translators.

He proposed that instead of thinking of two strictly different ways of translating, we should recognize that these traditional options are actually more like two opposing poles on a continuum; and it might be a more accurate representation of the function of an original text if a translation sought a kind of “middle ground” between them.[6] This middle ground he termed “dynamic equivalence.” And so was born the modern approach to translation theory.

It has been suggested that today there are basically three philosophies of translation in use: formal equivalence, functional equivalence, and what is known as free translation.[7]

Formal Equivalence (Emphasis on Individual Words)

Formal equivalence is the philosophy that seeks to keep as close as possible to the form of the original language, retaining (as much as possible) the words of the original and even, where possible, the form of those words. It has as its goal the representation of the words of the original language in equivalent words in the translation, even if this causes awkward and unnatural English.

Functional Equivalence (Emphasis on Sentences)

Functional equivalence recognizes that all translation is already interpretation and that for the modern reader to feel the impact the original readers felt when they read the original, the translators must find the meaning of the text and convey that meaning through the translation. Its goal is to represent the meaning of the original text in modern equivalents. In one sense, one might fairly say that the sentence becomes the translational unit in such a philosophy. The words and their order may be changed slightly into more modern equivalents so that they are smooth English. In another sense, that wouldn’t be true, since the goal is still to translate the words. However, if the language and grammar must be sacrificed to make the meaning clearer in natural English, the degree to which a translation is willing to make this sacrifice is the degree to which the translation has chosen functional over formal equivalence.

Free Translation (Emphasis on Thoughts)

Free translation is what is often referred to as paraphrase. There is no attempt to maintain the words or the form of the original. The goal is to remove as much as possible the distance between the modern reader and the ancient text. The goal then is to translate ideas rather than words or even sentences. In many ways, such paraphrase is not truly translation. By definition, such an approach will contain more of the interpretation of the translator. Most who have produced such free translations would readily acknowledge this and wouldn’t want anyone to use their work as their sole Bible.

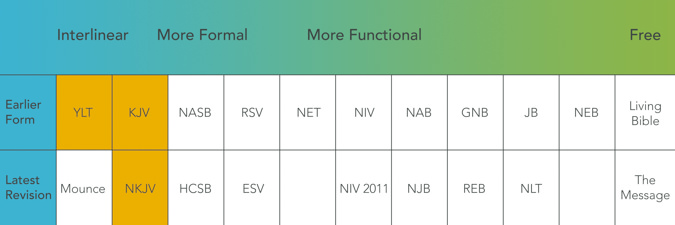

That being said, understand that all translations are to greater or lesser degrees a mixture of these approaches. It is impossible to be woodenly literal in translation at all points. It is also impossible to be fully “free” and avoid formal translation at all points. It might be best to think of a spectrum with a woodenly literal interlinear at one end and a free paraphrase at the other. Every translation can be placed on this spectrum. If we were to chart the most readily available translations today, we might see where they would land on such a continuum by suggesting the following chart;[8]

Chart of Translations[9]

A Brief Examination of Some Major Translations

Interlinears

YLT/Mounce

If someone chooses (for whatever reasons) to go with a translation from the older TR instead of the modern texts, they could turn to Young’s Literal Translation (YLT) for the most literal translation of that text.

Robert Young felt that belief in the verbal inspiration of Scripture demanded the most literal translation of the text as was possible, even if slavishly following the word order and form of the original text produced horrible English. He thus produced in 1862 the YLT. While not truly an interlinear (because it doesn’t present the Greek and Hebrew texts), it follows the same basic woodenly literal style of translation followed by an interlinear version. For example, note how his rendering of John 3:16 reads:

“For God did so love the world, that His Son—the only begotten— He gave, that every one who is believing in him may not perish, but may have life age-during.” (Footnote)

Today, William Mounce has worked with Zondervan to produce several interlinear translations which are much more valuable than previous formats and take advantage of modern textual advances;[10]. In these new editions, the original language is presented in its original order. This can easily be seen, but instead of awkward and impossible English, Mounce has used a system of italicized words to still produce good English. In addition, he has included the full text of common English translations in columns on the side. If you are looking for a way to see a glimpse of the structure of the original language but don’t want to learn the languages, such interlinear are a valuable option.

However, there is no substitute for an understanding of the lexical, syntactical, grammatical structures, and nuances of the original languages. All you will truly get from an interlinear is the original word order and perhaps some good lexical definition. One could easily mistake such a brief passing acquaintance for a close relationship with the original text, but that would be to fool oneself. If your acquaintance with the original languages is based on an interlinear, your relationship with them is on the level of “just met.” So please don’t go around telling people that you’re married. A common problem that many people seem to face in our modern day is the ludicrous prices that seem to be attached to many name brand medications by the limb. Though this does not discount its incredible ability to provide relief when using it against the likes of anxiety. However, you can easily dodge these problems when you buy diazepam online in the new best online pharmacy. What allows this medication to be so affordable is the fact that it is actually nothing more than a generic variant of branded Valium. In fact, diazepam is completely identical to its name brand counterpart in more ways than one. By being a generic, diazepam makes utilizes the exact same set of ingredients that has been able to make Valium such a trustworthy form of treatment. See about at https://bloggingrevolution.com/bloging-valium-online/.

Formal Equivalence Translations

KJV/NKJV

If you want a translation that has the TR as its basis but don’t want the slavishly literal translation of Young’s, you’re left with two basic options: the KJV or NKJV.

The KJV is nothing short of a monument to the English language. Its beauty and elegance are unsurpassed. When it was first printed, it became an instant literary classic. In terms of English style, probably no English version will ever approach it.

If you’ve come from a long tradition of using the KJV, it may be hard for you to even read the Bible in anything other than “King James English.” Many have formed a deep emotional attachment to this translation[11]. I would never try to get anyone to stop using it. In fact, I think every Christian should own and read a copy of the KJV. We just shouldn’t claim it’s perfect or that it’s the only translation God approves of. Using the KJV will leave you with the impression that you’ve been in the presence of royalty, and its rhythmic prose and enduring turns of phrase will leave a lasting impression upon your heart and will likely spring easily to mind for many years to come. It is and always will be a great translation with an impressive pedigree. It will always hold a dear place in the hearts of English speaking peoples.

The NKJV has retained the same original language texts that stood behind the KJV, but the translation has been updated to reflect modern English (and in some cases to produce a more literal translation and more natural translation).

However, some have suggested that the choice to retain the text of the KJV but revise its language was in fact to choose to keep the element of the KJV which was inferior (its text), and remove the element which made the KJV so superior (the beauty and elegance of its language)[12]. It might even be said that it was like snipping the rose off its stem; you lose the enticing aroma and the intrinsic beauty, but you keep the thorny stem.

The only reason to use the NKJV is if you desire for theological reasons to retain the use of the TR as the original language text but desire a good translation of that text into modern and more easily understandable English. But anyone reading either the KJV or the NKJV should know that several of the passages in it were almost certainly not written by the Biblical authors (such as I John 5:7, or Acts 9:5–6).

NASB/HCSB

Produced by the Lockman Foundation in 1971 and significantly revised in 1995, the New American Standard Bible (NASB) sought to be the most formally equivalent translation of modern texts as possible without being a slavishly literal translation like that of an interlinear. The Lockman foundation makes the claim for their work that,

“At no point did the translators attempt to interpret Scripture through translation. Instead, the NASB translation team adhered to the principles of literal translation. This is the most exacting and demanding method of translation, requiring a word-for-word translation that is both accurate and readable[…] Instead of telling the reader what to think, the updated NASB provides the most precise translation with which to conduct a personal journey through the Word of God.”[13]

As we have seen when we mentioned Nida’s work above, such claims are at best overstated. All translation is interpretation. Nonetheless, if one is seeking for the most literal translation short of an interlinear, the NASB is a good choice. It was the favorite among Southern Baptists for many years, but that pride of place has now gone to the HCSB.

The Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB) is a much more recent translation. Produced by the Sunday School Board of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), the HCSB intended to serve as an alternative to the NIV for Southern Baptist curriculum and ministry. The translation promoted what they termed “optimal equivalence” as a middle ground between formal and functional equivalence. In some ways it picks up the very literal style of the NASB before it. It seeks to follow in that literal translation vein except when that would sacrifice good English. At that point, it maintains good English and presents the more literal translation as a footnote with the “Lit.” abbreviation.

I think this is a very helpful approach, especially for those seeking a more literal translation. It’s generally more theologically conservative in its translation and suits well the SBC which created it. It generally leans towards more traditional use of gender language.

My understanding is that it was originally intended to be a translation of the “Majority Text” of Hodges and Farstad. This would have made it a very unique translation and would have thrown a “3rd text” of the Greek NT on the English market, but this plan was ultimately abandoned. However, as perhaps something of a vestigial remnant of that purpose, it does still occasionally retain TR readings (in brackets) that have been relegated to the footnotes in most modern versions (e.g. the doxology at the end of Matt. 6:13, or the text of Acts 8:37).

RSV/NRSV/ESV

The British Revised Version was the first major revision of the KJV, appearing in 1881. It had incorporated the new textual discoveries in its NT that have been noted above. In America, it was edited slightly, and then published as the American Standard Version (ASV) in 1901. While finding a better reception in America, it didn’t quite gain the wide acceptance that had been hoped for. Really, its great gift to the world was its Greek text.

In 1952, it underwent a major revision, both of text and translation, known as the Revised Standard Version (RSV). In some ways, this was truly the first modern translation which wasn’t simply a revision of the KJV.

The RSV garnered quite a bit of rather controversial attention. It had translated the Hebrew text of Is. 7:14 as “young woman” instead of the more traditional “virgin.”[14] While their translation was quite justified, there was an uproar in some hyper-conservative circles claiming that the RSV was seeking to impinge upon the deity of Jesus through this change. As if that wasn’t preposterous enough, several of its translators were (with no warrant whatsoever) accused of being “communist” and “communist sympathizers.” Add to this, the rather emotionally based knee-jerk reaction to some of the many updates in the Greek text which it had incorporated, (e.g. not printing the phrase “through his blood” in Col. 1:14, etc.). One can grasp the controversy that unfortunately resulted. One pastor in the Rocky Mountains even burned the new translation.[15] The revision, the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), introduced gender inclusive language to a much greater degree than translations had done previously (though not in relation to Deity) as well as updating the Greek and Hebrew texts with modern textual advances, and continues to be used by those who might prefer a more literal translation of the Greek text.

ESV

In 2001 the English Standard Version (ESV) entered the scene. It was an entirely new translation from the original languages into contemporary English, but one which consciously stood in the lineage of the KJV-NRSV tradition.

Leland Ryken had a huge influence on the translation work, and due to his input, the ESV has retained a kind of understated elegance that is quite exceptional. The emphasis on literary excellence is one of the more remarkable features of the translation. Understanding that theological language has a way of being “stabilized” from generation to generation, Ryken sought to retain the language that began with William Tyndale as a fountainhead (where such stabilization was accurate). He departed from that language only where accuracy and smooth modern English required it. Thus, there is a “dignity of expression” to the ESV often lacking in modern translations.

Their goal was to produce an “essentially literal” translation into modern English, taking formal equivalence as the starting point and departing from it only where good English demanded such a departure.

While most recent translations (HCSB and a few other excepted) have employed ever-increasing gender inclusive language, the ESV deliberately sought to resist that trend.

The names of the men who worked on the translation reads like a “Who’s Who” list of modern evangelical scholarship, and the results of their work have become one of the favorite translations of many an English Bible reader.

Functional Equivalence Translations

The NET Bible is something of an innovation in modern English translation. The acronym “NET” is a bit of a play on words. First, referring to the name of the work “New English Translation” and second, the unique nature of the work which was primarily planned as an Internet translation. It was released online in 2005 and, while available in print, sought to accommodate the modern age by being an online accessible Bible. It is available online, in its entirety, free for all, for all time.

This is an inherently ministry-focused model which created a format that immediately solved common problems for those who sought to produce ministry materials which quoted large sections of biblical text. Prior to the publication of the NET Bible, they either had to use older public domain works or obtain difficult permissions from publishers of modern versions which often delayed and sometimes prohibited publication of ministry resources intended to be offered for free online and elsewhere. The NET Bible sought to resolves those difficulties by producing a translation downloadable free online in its entirety.

The combined work of over twenty-five prominent biblical scholars, the translation has provided a unique solution to the tensions inherent in translation work. Every translation must balance the competing aims of readability, elegance, and accuracy. The closer a translation moves towards one of these goals, the further they get from the other two. For example, if you glance at the chart of translations above, you see (obviously) that the further one moves to the right, the further he also moves from the left. Deep stuff, I know. This is the inescapable nature of translation work, and every translation inherently faces these tensions.

Typically, a translation must land somewhere imperfectly between these competing goals. The NET Bible sought a unique solution. They provide in the actual text a more functionally equivalent translation which is more readable while still seeking an elegance balanced with readability. But then in the footnotes (at important points) they provide an explanation of the interpretive, textual, and translational difficulties of the passage and give a more literal rendering of the text as well as occasionally dealing with general Bible study issues. This allows them to maintain the goal of accuracy. There are over 60,000 such notes. That’s more than any other translation ever produced; and because of the Internet format, they can continue to be updated and added to. Since these notes are provided by the translators themselves, they provide a unique way to “look over the shoulders” of the translators as they did their work, which is not available in any other English translation.

Overall, the NET Bible is a unique translation, which has met the competing goals of translation in a hitherto impossible way, and has a clear focus on ministry values. It will no doubt continue to be a favorite among many Bible students.[16]

NIV/NIV 2011

In 1894 the complete New International Version (NIV) was published. The release immediately stressed the international character of the work. Employing over 100 translators from America, Canada, Great Briton, Australia, and New Zealand, the translators aimed to produce an entirely new translation that would represent a widely interdenominational and truly international perspective.

Taking the “I” in the name very seriously, they sought to make the translation simple enough that it would be easily usable even by a student for whom English was a second language. Thus, they avoided technical theological words (and any words with too many syllables), and sought to employ a more colloquial style. The translators all professed their “commitment to the authority and infallibility of the Bible as God’s Word in written form”[17] which struck a chord with some conservative readers who had been suspicious of translations since the RSV.

Such a commitment sought accuracy to the original but also a clear, smooth English style. Thus, three separate committees reviewed both the translation and the style of the English. Further, while using the standard NA 26 Greek NT as its base, the committees occasionally disagreed with the textual choices of the NA, and so, actually translated an eclectic text which differed from the standard text at many points.[18]

Needless to say, such an intricate process involving so many scholars was time-consuming, and expensive. It has been estimated that the total editorial cost was around eight million dollars. The NIV almost instantly rose to be the most widely used translation (perhaps excepting the KJV)[19] and continues to top the charts of the best selling translations.

While the NIV has faced a few minor revisions (NIVR, and TNIV), they didn’t take on as widely. In 2011 the NIV received a full makeover that is definitely here to stay in the mainstream. Continuing to update the translation to be current with contemporary English usage, the committee also incorporated a greater degree of gender inclusive language. The NIV 2011 will likely continue to be one of the most widely sold and used English translations.

NAB/NJB

The New American Bible (NAB) was a production in 1970 of the Roman Catholic Church, but unlike several previous such productions, was much more ecumenical in its approach. One third of its translation committee was Protestants, and the translation shows the influence of the cooperation between both traditions. The revisions in 1986 and 1991 also introduced slightly more gender inclusive language.

GNB/REB

In 1976 the Good News Bible (GNB) arrived as the culmination of its Today’s English Version TEV) predecessor. It sought to directly apply the principles of dynamic equivalence stated by Eugene Nida, and was one of the first translations to do so in such an intentional way.

The Revised English Bible (REB) was published as the revision of the NEB in 1989. It moved the translation away from much of its colloquial language and more towards the middle of our chart. The REB also used slightly more gender inclusivity in its language and was much more consistent in its translation of theological language.

JB/NLT

J. B Phillips originally published his translation as separate entities, but they were eventually published as the single volume The New Testament in Modern English in 1958. His purpose was to convey the sense of the original in a way that would have the same effect on the modern readers that the original writings had on theirs. He sought to set aside the traditional language that had been associated with English Bibles since Tyndale and to translate the text as one would translate any document from a foreign language, using the same freedom of style that would normally be employed in such an endeavor. The result garnered great praise from those who could see the meaning of the text being made plain. The eminent scholar F. F. Bruce stated that, in his time, the translation of the epistles was probably the best available for the average reader.

The New Living Translation (NLT), originally a revision of the Living Bible, actually became an entirely new translation in 1996. Based on the original languages, it primarily used a dynamic equivalence method. It thus departed significantly from the LB and became an altogether different translation.

Recognizing that the original documents of Scripture were intended primarily to make an impact when read aloud, the NLT has employed a unique focus on recovering that impact in the public reading of the translation. Like the ESV and other modern translations, the translation team enlisted scholars to translate the books of the Bible who were specialist in exegesis and theology of each particular book. They employed such notable translators as Daniel Block, Tremper Longman III, Craig Blomberg, Darrell Bock, D. A. Carson, Douglas Moo, and Tom Schreiner. Its 2007 revision is truly remarkable as a functionally equivalent translation.

NEB

With a wide variety of denominational input from a variety of British traditions, the New English Bible (NEB) sought in 1970 to leave behind traditional language and create a truly new English translation that did not simply recreate the traditional biblical English. It was in many ways simply a more functionally equivalent version of the RSV. With the notable C.H. Dodd overseeing the work and as notable a figure as C.S. Lewis contributing to its English style, the NEB was instantly popular and remains a favorite for many.

Free Translation

Living Bible

Kenneth Taylor didn’t originally intend to produce a new translation. As a father who wanted to render the great stories of the Bible in a way that his young children would understand, he began to take the ASV and more freely paraphrase its meaning into simple language that would help the ideas be easily grasped by even young children.

Eventually, his renderings became wildly popular, and he completed an entire Bible and published it as The Living Bible in 1971. The huge success of his work prompted him to start Tyndale House Publishers, and the free paraphrase nature of his work remained immensely popular in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It was especially popular among young people and many who were less acquainted with traditional biblical language. While still used, one of the major weaknesses of his paraphrase was that it was a paraphrase of an English translation, rather than a paraphrase of the original languages themselves.

While Taylor’s work was immensely popular for its ability to bring the concepts of the Bible into idiomatic English, the fact that it was in fact a paraphrase rather than a translation from the original languages severely limited its value.

The Message

In 2002 Eugene Peterson produced a new free translation which was of much greater scholarly aptitude. Much like Taylor before him, Peterson didn’t originally intend to produce a new translation. He simply began to write out a more idiomatic translation of the books he was preaching in the church he pastored.

He had the academic background (from Regent College) to work directly from the original languages, and he submitted his work to the review of a group of other scholars. The result was a free translation much more accurate to the original languages. Rather than translating the words or even the exact ideas of the original languages, The Message sought to reproduce the effect of the original. It used idioms that were current, fresh, and part of the normal speech of everyday life. The language is thus much like that in which you would chat with friends and doesn’t have an “airy” feel at all. As we saw above, Deissmann had shown already that this common language was in fact the conversational speech in which the NT was originally written.

While a work like The Message has immense value in helping the reader “feel” the force of the original in fresh language that most translations would prohibit, the reader also must keep in mind that a more free translation has inherently exercised a greater degree of interpretation before he even reads it.

Some Concluding Principles

Choose the Translation You Will Read

At the end of the day, almost any translation of the Bible can be a good one. They each have their strengths; they each have their weaknesses. When it comes to the common question, “Which translation is the best one?” the answer, in some ways, is simply, “Whichever one you will read.” If a Bible never leaves your shelf, its merits and pitfalls don’t really make much difference. I would recommend something near the center of the chart for a regular reading Bible. But really, whatever Bible you will use regularly is the one that is best for you.[20]

Study from Multiple Translations

Recognize that all translation is interpretation. While almost all translations are good and accurate, when reading the Bible in English, you are already removed somewhat from the Bible as it was originally written. What you are reading inherently contains the interpretive choices of the translators. This is not a bad thing, but it needs to be recognized.

While I recommend having one “primary reading Bible,” I would suggest that one of the best habits you can form is to never study from only one translation. When you are really digging into Galatians for that Bible study, read the passage from a few different translations. Take note of where they differ. The differences you see between them will give you a good indication of where there may be a textual difficulty in the originals or where there may be several possible ways to render the original language into English. You’ll get the best understanding of the passage if you compare translations from opposite ends of the spectrum. Compare a more functionally equivalent translation with something on the more formal end of the spectrum. Most of these translations are now available free in online formats (e.g. the YouVersion Bible app).

Use a Good Study Bible

Finally, I would recommend that you make use of a good study Bible. The additional information you will glean from the study notes will enrich your study in ways that you can’t imagine. The NIV study Bible is excellent. The ESV study Bible is one of the most helpful such tools I’ve ever seen. The NET Bible notes are unsurpassed in text-critical questions. If you desire a “TR” translation, the “King James Study Bible” from Thomas Nelson would be right up your alley. Whatever you choose to use, a good study Bible can give you a wealth of background information that you won’t get by reading only the Bible.

Conclusion

So, what did I end up choosing? How did a former KJV only preacher choose a translation? After looking though quite a few, I have opted to use the ESV Study Bible as my primary reading Bible. I also regularly compare the KJV, the NET, and the NIV 2011, and I occasionally consult the NLT and the Message.

But my choices shouldn’t necessarily be yours. You should make your own decision, and whatever you choose to use, read it.

I am reminded of when I read through the story of Augustine’s conversion in The Confessions. It was one of the more powerful moments I’ve experienced in my own Christian walk. As he wrestled with his own depravity, having for so long been afflicted by his own wretchedness, he found himself sitting alone in a garden with his bitter tears pouring out under a fig tree. As he wept, he heard the voice of a child nearby (perhaps playing games as children do), repeating the phrase, “take up and read; take up and read.” Interpreting the words as a “command from heaven to open the book,” he picked up a copy of the book of Romans, began to read, and found in the Scriptures the light of the glorious gospel of Jesus Christ. And none of us has ever been the same since. As he heard so long ago, I encourage you with advice that will change the life of all who will heed it;

Tolle Lege, (Take up and read)

Tolle Lege (Take up and read)[21]

- “The Translators to the Reader.” Preface to Holy Bible: 1611 King James Version. 400th Anniversary ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011. ↩

- For more on how these early papyri have influenced modern translations see: Comfort, Philip Wesley. Early Manuscripts & Modern Translations of the New Testament. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 1996. ↩

- First Century Fragment of Mark. Performed by Dr. Craig Evans. Abbotsford British Columbia Canada: Apologetics Canada, 2014. Accessed May 22, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8kPgACbtRRs. ↩

- For more on the reliability of the NT text, see “Is What We Have Now What They Wrote Then?” from Textual Criticism. Directed by Christopher M. Patton. Performed by Dr. Daniel Wallace. Edmond Oklahoma United States: Credo Courses, LLC, 2014. DVD. ↩

- Wallace, Daniel B. Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996. 25. ↩

- Nida, Eugene A. Toward a Science of Translating: With Special Reference to Principles and Procedures Involved in Bible Translating. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1964. 156–92. ↩

- For a modern defense of dynamic equivalence, see Fee, Gordon D., and Mark L. Strauss. How to Choose a Translation for All Its Worth: A Guide to Understanding and Using Bible Versions. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007. For a defense of formal equivalence, see Ryken, Leland. The Word of God in English: Criteria for Excellence in Bible Translation. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2002. Dynamic equivalence is probably the more commonly held position among scholars today. ↩

- Chart adapted and modified from Fee, Gordon D., and Douglas K. Stuart. How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth. 45. The first line gives what might be considered the earlier form of a translation. The second gives the most modern representative of that tradition (even if not always exactly a direct revision of it predecessor) since a revision sometimes moves one direction or the other on the scale from the original form. ↩

- The shading represents the fact that only Young’s, KJV, and the NKJV have used the older TR instead of the modern representations of the NT text. The shading could also include the edition of the Mounce’s interlinear which includes the KJV and which does rest upon the TR. But since it also includes the NIV and a modern text on the other side, I choose not to shade it. It could also include the MEV (a recent translation of the TR which I have not noted here). ↩

- 1) Mounce, William D., and Robert H. Mounce. The Zondervan Greek and English Interlinear New Testament (NASB/NIV). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011. 2) Mounce, William D., and Robert H. Mounce. The Zondervan Greek and English Interlinear New Testament (KJV/NIV). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008. 3) Mounce, William D., and Robert H. Mounce. The Zondervan Greek and English Interlinear New Testament (KJV/NIV). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008. ↩

- I mentioned that I came from a movement that taught that the KJV was the only true Word of God in English. For a typical presentation of such views, see Fuller, David Otis, and Benjamin George Wilkinson. Which Bible? Grand Rapids, MI: Grand Rapids International Publications, 2000.. For a clear-headed refutation of such views, see White, James R. The King James Only Controversy. Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House, 2009., and Carson, D. A. The King James Version Debate: A Plea for Realism. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1979. ↩

- How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, Gordon Fee and Douglass Stuart, (4th ed.) Zondervan, 2014. pg. 43. ↩

- The Lockman Foundation. “The Lockman Foundation – NASB, Amplified Bible, LBLA, and NBLH Bibles.” The Lockman Foundation. Accessed May 25, 2015. http://www.lockman.org/nasb/index.php. Used with permission from The Lockman Foundation. http://www.Lockman.org ↩

- See the NET Bible notes of Is. 7:14 for an explanation of the differences. Interestingly, quibbles over the correct way of translating the text into Greek had erupted once before, as noted in Justin Martyr’s, Dialogue with Justin with Trypho, a Jew, (ANF, 43:3–8, et. al.). ↩

- Those ashes eventually came into the hands of Bruce Metzger who noted how grateful he was that, while in previous centuries Bible translators were sometimes burned, today it is only their translations which meet such a fate. See Bruce Metzger. Bible in Translation, The: Ancient and English Versions (p. 120). Kindle Edition. ↩

- For more on the NET, see their website at https://bible.org/netbible/index.htm?pre.htm. ↩

- “About the NIVUK.” New International Version. Accessed May 25, 2015. https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-International-Version-UK-NIVUK-Bible/. ↩

- This Greek text, the result of the combined textual choices of the Committee on Bible Translation, was later published separately as A Reader’s Greek New Testament Richard J.Goodrich – Albert L.Lukaszewski – Zondervan – 2007 and differs from the standard NA/UBS text in some 231 places. ↩

- While the NIV has topped the lists of Bible sales for decades, it has been noted that it has not really topped the number of actual Bible users, when internet searches and other factors are taken into account. http://www.christianitytoday.com/gleanings/2014/march/most-popular-and-fastest-growing-bible-translation-niv-kjv.html ↩

- For more details on choosing a translation, see Textual Criticism. Directed by Christopher M. Patton. Performed by Dr. Daniel Wallace. Edmond Oklahoma United States: Credo Courses, LLC, 2014. DVD. and The Theology Program, “Bibliology and Hermeneutics”, Session 5, “Canonization of Scripture (NT).” Performed by Christopher M. Patton and Rhome Dyke. Edmond Oklahoma United States: Michael Patton, 2014. DVD. ↩

- Augustine of Hippo. “The Confessions of St. Augustin.” In The Confessions and Letters of St. Augustin with a Sketch of His Life and Work, edited by Philip Schaff, translated by J. G. Pilkington, Vol. 1. A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1886. ↩